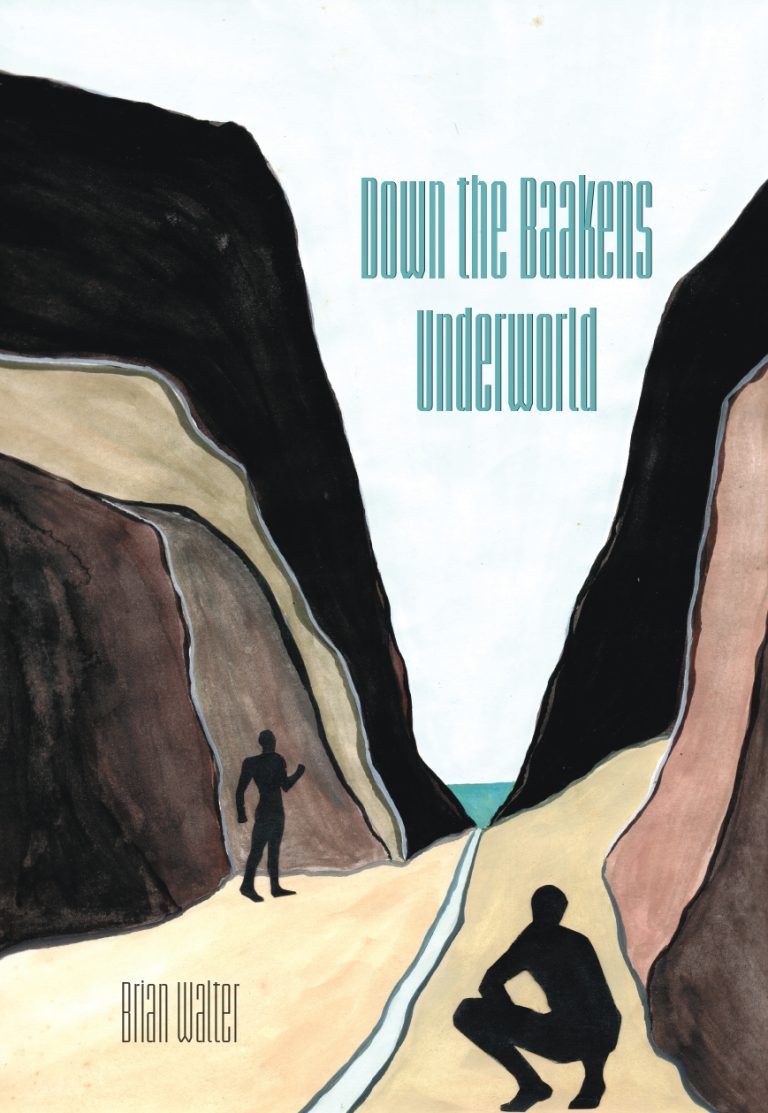

K. G. Goddard, author of Notes from the Dream Kingdom (Botsotso 2025), speaks with Brian Walter, author of Down the Baakens Underworld (Botsotso 2024) about his practice.

1. Why have you chosen to write poetry? Why not another genre of writing?

Poetry just happens to be where I am most comfortable, where I’ve managed to find some sort of voice. I tend to observe or conceive of things with or through the lens of a poem now. If I recall an incident, or a landscape, that’s the way it comes to me, not as a nascent novel, or drama. And if a poem is not enough, I write a second poem. I think, in this text, the Baakens section can be read as one poem.

2. What role, do you think, can white male poets play in contemporary South Africa? Should we be concerned about race and gender in the publishing of poetry?

Through my life experiences I’ve learned to dislike categorization and stereotyping, from which much harm has come. Humans are complex and multifaceted. Under apartheid I have, for instance, been officially categorized as white (not something I have ever properly understood, nor – when I knew better – related to) and educated accordingly. I was separated from compatriots, and taught languages at the expense of the local African language, Xhosa. At a male-only high school, I struggled through adolescence, wondering who was who and what was what. Girls my age were at different schools. Thus, race (including language and culture) and gender classification were limits on my humanity, and I’ve tried to broaden my understanding and being since.

My life experiences have helped me to not consider myself as a racial category, though I’m aware that others may see me in certain ways, depending on their own frame of reference. I understand the concept of whiteness, and what has been done in the name of this dreadful idea (as well as in the name and practice of toxic masculinity).

In terms of publishing – what is being read, or available for reading – I would, were I a publisher – try to promote good poetry by a diversity of voices: and, if I had the capability, a diversity of languages, too. If I had any leanings or preferences, it would be to humanistic voices: voices of kindness. This is not as soppy or easy as it sounds. Lear is a play about kindness – of what happens when Cordelia, the heart, is exiled. The children in Gaza need kindness. The children in many of our schools need kindness. Perhaps to evaluate writers by race or gender is both unnecessary and unkind. To be called a “white male poet” somehow suggests one “stands for” or speaks for those things: I don’t.

3. Should poetry in contemporary South Africa be political/social, or can it be largely personal and contemplative?

Poetry is a human mode, and I would hesitate to say what it should be or not be. Once I was discouraged, mockingly, for writing poems about the natural world: now the fashion has changed. So, who’s to say? But, if you are human, and write about human things, and live in a country like South Africa – or Gaza – how can you miss the political and social unkindness all around? I was once told at a reading of the original Baakens text that the book was largely about “white guilt”. The racial laws and breaking up of communities are part of the poem, and the idea of forgiveness is a theme, a thread I picked and unpicked through the poem: but “white guilt”? It was another of those moments when, looking back, one sees the poet standing with binoculars in hand, like a fool. If I were writing about white guilt, I’d stop writing. One sees what is, and what bothers one.

I remember reading Walcott on one of my favourite poets, Robert Frost. He suggests that Frost, in his pastoral, agrarian focus elides over the darker aspects of American history: slavery, dispossession. Indeed, one would not go to Frost for these things. I don’t think you’d turn to my poetry for such things, either. But in my verse, I hope you’d find the scars on the landscape, the knowledge of deep unkindness, the need for the impossible forgiveness. If you are writing in South Africa, you should be aware.

4. There seems a great proliferation of poetry in South Africa right now. Can you suggest some reasons why?

There is much writing of poetry, and this shows a valuable need to express thoughts and be creative, both amongst young and older writers. But alas, reading poetry is very slow. Buying poetry is slower still. Publishing poetry depends – for commercial firms – on buying. This is a truth poets must accept: people buy what they like to read and want to go back to. A poetry book that is read once, and never again, is not good value for money. It won’t change, I guess. Can one write poetry that is enjoyable for people to read, but that still is uncompromisingly honest, and oneself? For poetry beyond the commercial firms, government or other support seems imperative. But there is a great need to encourage reading in the country: in schools and out of schools. There are many things working against reading, these days, beyond the digital revolution…

5. Your poems show a strong ecological focus. Why?

I guess my upbringing. My father grew up on a farm near Cullinan, before he moved to Gqeberha, then Port Elizabeth. His own father was a farmer, a horticulturalist (Athol Fugard’s brother was an apprentice under him) working at Victoria Park (where a road is named for him), before doing the gardens and grounds at Rhodes University – where he planted many of the cycads, and Cape chestnuts, I believe. Our own father took us into the countryside, took us to game reserves. My older brother is a zoologist, and all his life has been watching birds. So, I like gardening, birds, trees, the outdoors.

When one watches what has been done to the earth, to patches of land, to rivers, one despairs – a study of the many rivers and streams running into Algoa Bay would reveal the extent of the harm. I was reading old accounts of the bay recently – in one the botanist Carl Thunberg describes the Khoi people he encounters. But he also describes herds of buffalo “five or six hundred” strong in an area we still call Kragga Kamma after its fresh waters, and he describes seeing and hearing lions. Or a description of masses of flamingos at the mouth of the Papenskuil River, a lagoon then, now a concrete channel – an abomination. Imagine the landscape, with elephants all the way from the Cape, through Knysna, to Gqeberha; with buffalo all over, the Cape lion, the quagga. The extinct blue antelope. Me – I look at what we have, at wagtails roosting in the trees near my local. And I work my garden. But I think a lot about the land, the earth: my poetic is earthy – “my mistress when she walks treads on the ground”.

6. Do you feel a need to recapture a relationship with the land that we may have lost?

I think a proper awareness is important. I don’t know what “proper” means here: for me it’s one thing, for others it will be another. There’re awful issues of ownership, and who owns land, and returning land. I hope that whatever comes of this, land is not treated as mere commodity. In Okara’s The Voice there are two messengers walking with shoes that are basically the bribe given to them to take a message: their feet become sore with the new shoes, and they eventually take them off, reconnecting with the real, the earth. I think we need to take our shoes off and realize the land – with all its rooted growth, and stones, and thorns.

7. Your focus is also strongly on the Eastern Cape. Is that only because you live here, or is it a more considered choice to emphasize a particular place?

It is because I live here, firstly. My writing tends to be grounded, rooted in experience. To express this fancifully, as suggested above, my muse – like Shakespeare’s mistress – walks on the ground. But, more broadly speaking, the Eastern Cape is, as I have called it in “The Cuckoo and the Eastern Cape Quest”, a “cradle of conflict”. The Eastern Cape I have lived in is a microcosm of South African history, of world history, from the old stonework fish-traps at Cape Recife, the name Kragga Kamma, to the mission station in Bethelsdorp, up past Makhanda, along the military road through the Ecca pass to Fort Beaufort, along the sites of the battles of the Colonists with the Xhosa.

My early life was a childhood and education in an apartheid world of white Port Elizabeth; then during the apartheid years I worked at Chapman High School in what was deemed a “coloured group area” in Gelvandale, where I made friendships which I have to this day. I discovered the split personality that comes from being South African, something I am still trying to heal, both in myself and in my writing. Then up to Fort Hare University, where I was able to engage with a whole new, deep side of South Africa. I also met other writers, and the artist Hilary Graham. We started an informal group of poets, now called the Ecca Poets, which is still writing, with a blog and a book a year. While at Fort Hare, I married a woman whose family had been moved from South End. So, yes, I write from what I see around me. And it is enough, and more.

8. Tell us a bit about your personal history with the Baakens river and why you felt you wanted to use it as a symbol/metaphor in the poems.

As a kid growing up in Glen Hurd, between the valley and Newton Park, we thought nothing of wandering down into the valley. It was an extension of our playground. I loved it, and it gave me a lot – the white cliffs, the reeds, the birds. But the reason I tackled it was through conversations with Cathal Lagan, Irish-born South African poet. He taught with me at Fort Hare. And when I had written the Swartkops poems, near the front of this current book, he urged me to write more. I didn’t want to add to what I’d done and tiredly told him one day that if I wrote about a river again, it would be the Baakens. So he began to ask questions about why, and what, and so on. The more I spoke to him, the more complex the valley of my childhood became. And the series of poems grew, till eventually we did a walk – he and I and family – from the Third Avenue dip below Fairview, along the river, and up to Fort Frederick. I used part of his urging and questioning as an element of the ironic guide figure in the series of poems and dedicated the book to him.

9. In the poems, even the earlier ones, you are often the poet/eye observing the landscape, but also the one observing himself observing … a kind of “voyeur” as you put in in one poem. How would you define your poetic relationship with the landscape? Observer, participant, trying not to be its controller?

In the first of the Swartkops poems, a woman selling bait wades across the river to sell to a person, the poet, watching birds. As she returns across the river, she looks back – and there she sees a birdwatcher, with binoculars, looking “like a fool”. Leaving the underworld, leaving Sodom, looking back is forbidden. So it’s a complex thing, this being in the landscape, being both separate and a part of it. Seeing oneself as observer…

In the last poem in Shades of St Francis – and St Francis’ kindness extended to animals, birds and the natural world – there is an image of poet as gardener: rather ineffective, with words put out of the garden, like Adam and Eve. Ineffective because uncertain, perhaps, tentative… in that poem the speaker says “I am neither priest nor politician / no people’s poet budding profusely”: the speaker “inches” out a verse.

So certainly not a controller – who dares? – but seeing, reading the landscape. Our history is written here, as are the elements of our future: fences, buildings, foreign trees, crops, dams, shantytowns, graveyards, apartheid spatial planning…

10. The landscape carries political and social history in many of the poems, but it also seems to carry something of the numinous for you. Sometimes it is mystical and sometimes threatening, like a dark creature rising from the underworld. Sometimes you depict it as a place of “reckoning.” Can you say more?

To cross the landscape, to journey, is to find oneself – as your own work shows, we are travellers, pilgrims – travelling through, across, towards. In the section Allegories, Section xi of The Guineafowl Trail, there is a phrase I used about things seen on our journeys: “these telling allegories of our everyday”. I used that phrase before thinking about it more deeply: it finally gave me the title of a book Dryad Press published Allegories of the Everyday. I think – returning to the earlier question on my mode of writing – this finding of allegories in the quotidian, thinking through things, extracting or invoking architypes, seems to be my mode of making sense so that the valley walk becomes a journey to the underworld, a place from which one looks at the past, a place of discovery, of judgement, of understanding history, oneself…

11. At the same time the land is a reckoning, its meanings often seem elusive, like the time and sand in the hourglass image. Is the landscape a muse dragging you deeper into itself, or into a version of you going deeper into your unconscious? You talk elsewhere of the “old reptile dream.” Are you going back in time and down into an earlier, more primal self in the Baakens? What is the nature of that primal self?

That image comes from the section called The Spinner, the name of one of the Fates, so yes – the journey and its meanings are elusive, the uncertainty of self through the history and mysteries of the landscape. The Baakens is particularly interesting to me, because it’s not a long river: Its source is up in the old grasslands or vlei-lands on the hill, and the source seems to speak of an essence, a core being – a primal self, if you will. But the early seafarers put a beacon (whence the name Baakens) near its mouth, signaling a place of refreshment on their own journeys. The guide-figure in the poem points to the beacon as the place of meaning, the poet-figure traveler seems to want to go, rather, to the source. The indigenous, the earthy – away from easy meaning, perhaps? “Beacon” has, I seem to recall, the same root as the word “beckon” – the temptations.

12. If the land is the psyche and also history, how do you penetrate it? Or can’t you? How does it penetrate you?

I can’t think of “penetrating” as a way of finding understanding. It is too masculine, or colonial (to use current tropes) – one can only glean some sort of meaning from the journey, depending on whether one takes note or not. For me, reading and writing poetry have become some way of taking note: being aware, reading the allegories. I feel much more like Keats’, seeking to “be” in uncertainty. If I recall his letter correctly, he speaks of “becoming” a sparrow, not merely seeing it: there’s an imaginative leap there. And of course, the sparrow is merely an example of one thing observed on a journey. In Okara’s novel, The Voice – I haven’t read it for a while, and I think I need to go back to it – that main character, the quester, is looking for it. Whatever that is – the truth, or values, integrity, or his “inside”, it is never defined. Okara also, in this novel and his poems, has a wonderful sense of a god – an idol, not moving and inscrutable. It’s very stone-like lack of movement emphasizes the mystery. Yeats speaks, in A Prayer for my Daughter, about the dangers of opinions and “intellectual hatred”. We live in a world full of opinion and “intellectual hatred”. Perhaps Keats’ being imaginatively one with something, or someone, enables a greater kindness.

13. “I was become succulent by way of being” suggests a fusion of self with the land and yet not a complete fusion. One still struggling to happen. And that “succulence” is of “remembered sin.” Why sin? The pure landscape can reveal the sin in us when we encounter it fully?

In the fictional world of that poem the Karoo is like a wasteland, with the sun burning off sin as the Everyman figure is called to account – it’s a journey towards a place of death, of knowing. The journey leads towards four poems I did for a project with artist Elaine Matthews.

14. Your poems retain a certain metric formality, and you enjoy using half-rhymes, as if to savour the pleasure of sound and cadence. Is this intentional, something you work hard at, or does it just flow naturally?

Mostly worked at, I guess. Though, as I said above, writing tends to enable a writer to grow a lens, a mesh, through which one sees the world. Sometimes things come happily along, but at other times they are worked at and turned and twisted until they sound right. I edit a lot. I find two important phases of my writing. Perhaps three. The first phase is the first thoughts, the idea – down on paper; the second is the editing. I find sometimes I enjoy this the most, the playing with ideas and ways of expressing, until things fall into place – at least for my ear. The third phase is trying to find a home for the work, some publication. This is sometimes the most difficult, and one has to work on this. I have learned to work on this – no one else will – but it is the least creative of the writing process for me.

15. Lastly, can you say something about your long involvement with young poets from Helenvale and Salt Lake in Gqeberha, very violent zones. Have their lives and experiences affected your own poetry significantly?

I spoke earlier of my own growth as a human, and as a South African. An important step for me was moving into a job in Gelvandale, at a school called Chapman High School. I taught there for a few years, my first teaching job. After a stint at the Herald newspaper, my first full-time job. This experience changed my life, changed it utterly. If you are brought up in anything like white South Africa – or its many equivalents, heaven forbid – you are raised to see people in stereotypes. Working at Chapman, teaching people who were – I realize now – were not too much younger than I, was a lesson to me, in humanity, and in humility. I discovered not others, but people who I came to love and value. I still see some members of the class I taught and am still friends with some of my colleagues. I discovered kindness – acceptance when politics made it hard for people to accept me.

When I returned to Gqeberha after teaching at Fort Hare, I was involved with community work and with education projects. Happily, they came together, and I raised funds for a poetry project. The initial idea didn’t work out, and it was suggested by the NPO I work for that I try in Helenvale. A few community meetings later, and some false starts, and we found a group of five who worked on our first book. Key amongst those was the late Byron Armoed, a community worker, who unbelievably was gunned down, and Leonie Williams, whose really earthy poems deserve more attention.

But younger poets started coming in. Nearby Gelvandale gave me a lot and taught me wider humanity. I feel that I am giving what I can in return. Helenvale is hard: it’s a struggling community – I sometimes say it’s a condensed Cape Flats – its violent. The kids – all of them – have seen dead people on pavements. They laugh if I say that that is not normal. But the best I can do is encourage them to write, and to be human in my dealings with them. We have been going for about 14 years, with a book a year; and the newer Salt Lake Poets have three books. It’s a labour of love with the emphasis on both labour and love.

My biggest worry is fund-raising, and the fact that I’m not getting younger.

Again, for me, it’s finding humanity beyond the stereotypes. Stereotypes imposed by others, but most unfortunately becoming learned and self-imposed. I weep for the children I work with, and weep more when they grow older. They deserve better than they get. And I suppose that’s why I keep at it.

Brian Walter’s Down the Baakens Underworld is available via African Books Collective. Botsotso Publishing is made up of a group of poets, writers, and artists who wish to create art and to generate the means for its public communication and appreciation. They speak particularly of art that is of and about the varied cultures and life experiences of people in South Africa – as expressed in all languages. To find out more, take a look at their publisher page.