Anshita Ail interviews Sarah Uheida of Not This Tender, published by Dryad Press, about her poetry collection Not This Tender, a deeply resonant meditation on memory and displacement. The collection traces the terrain of war-ravaged North Africa, which Sarah Uheida was forced to flee as a child, weaving together the mythical and the intimately personal. It explores themes of longing, belonging, estrangement, and loss, shaped by the forces of family and language. Through striking imagery and fragmented landscapes, Uheida’s poetry becomes both a sanctuary and a site of rupture, an act of excavation not to enshrine the past but to illuminate the path ahead. The result is a haunting, lyrical journey through the ache for home and the fragile, persistent hope of return.

What draws you to poetry as your primary mode of expression? What can poetry do that other forms of writing can’t?

Poetry seems able to adapt to thought. It allows breath, image, philosophy, and intimacy to live side by side. I’m drawn to its precision — but also its openness, and how it doesn’t rush to resolve. It lets language hold weight and lightness at once. It can pause, fragment, cut, or bloom — all in a single line. There’s something deeply physical about it, too: you feel your way through a poem, like you’re walking through a mind that’s halfway lit. It allows me to reach for clarity without certainty.

Many of your poems feel deeply personal. How do you navigate the tension between vulnerability and privacy in your work?

I try to approach vulnerability as a form of clarity — to write from what feels emotionally accurate, even if the details are layered or imagined. Even in poems that carry pain — especially metaphysical or familial pain — there’s an instinctive editing that happens: what’s too private stays private, but what’s true stays in. I trust the reader to feel what’s real, even in what’s been crafted, and to decide how much of it to carry. “Tension” is a good word here. Without vulnerability, there’s no poem. But without some form of restraint — linguistic, emotional, or structural — the poem can’t hold. The craft is the threshold.

Themes like family, memory, grief, and cultural inheritance recur throughout your poems. Do you consciously return to these ideas, or do they find you?

Sometimes they rise without warning. Other times, I go to them deliberately. I stay curious about how grief evolves, how memory changes shape, how family morphs as we do. There’s always more to ask, more to feel. And poetry gives you a form in which you can try to listen better. These themes keep opening — not as repetition, but as variation.

Your work moves between mythology, religion, and personal history. What kind of stories or traditions shaped you as a writer?

I grew up surrounded by Arabic — where language carried religious weight — and Libyan dialect, which is oral, musical, and rarely written. So I was shaped by both scripture and song, metaphor and memory. I was also raised in a context where language had to do a lot: announce, comfort, warn, translate. Before I even began writing poetry, I was absorbing a poetics of survival. The more I reflect now, the more I see how Berber myth, exile, and inheritance have been embedded in how I think — and poetry gives me a way to sculpt those into something that might make sense together.

Who are some of the writers, artists, or thinkers who have influenced your voice or approach to poetry?

The Argentinian poet Alejandra Pizarnik gave me permission to explore the self and interiority without the guilt of seeming “self-centred.” Middle Eastern authors Nizar Qabbani and Mahmoud Darwish offered a language of homeland and longing I didn’t yet have access to, but somehow already recognised. I return often to Hélène Cixous, Djuna Barnes, Clarice Lispector — women who link language, intimacy, and the feminine body. Lispector gave me silence and intensity. Barthes taught me that thought can be sensual. I carry Ocean Vuong for his musical precision, and Ada Limón for her elliptical clarity. These are writers who don’t separate feeling from form. I don’t think I want to, either.

Much of Not This Tender comes from your experience of leaving Libya. Does writing about that departure keep you tied to the past or open new ways of seeing the present?

Maybe both. Maybe neither. I keep writing to find out. The departure isn’t a single moment I revisit — it’s a solid memory that keeps changing shape. When I write about it, I’m not staying in the past; I’m revising it, reframing it, asking new questions from wherever I stand now. Writing keeps it in motion. I do believe the future needs the past to happen — and poetry allows me to visit and revisit memory in a way that feels both alive and manageable. It gives me a language in which I can mourn and move at once.

Can you speak about the moment or experience that initiated this work? Was there a specific poem that opened the door for the rest?

Most of the poems in Not This Tender were written across years. I’d wanted to gather them for a long time, but I didn’t have the name yet. In October 2023, I did a reading at The Red Wheelbarrow in Cape Town and decided to read a short poem I’d written that day, called Overstay Appeal. It ends with the line: “I have wanted to be many things, but not this tender.” I remember stepping outside after the reading and thinking: this is it. That’s the title. That’s the feeling. A year later, I heard the incredible news that Dryad Press would be publishing the book — a dream, really, since I’d always hoped my debut would be with them.

Memory, displacement, and cultural connection are central to Not This Tender. How do you balance honouring your heritage with adapting to life in unfamiliar places?

I try to write from simultaneity. The more rooted I feel in the present — and South Africa has been home for 14 years now — the more I can look back without collapsing. That, to me, is what healing might be: the ability to look back. Poetry helps me hold those threads together without needing to untangle them too quickly. I don’t try to “balance” past and present — I try to let them speak to one another, to coexist, to reveal what each one needs from the other.

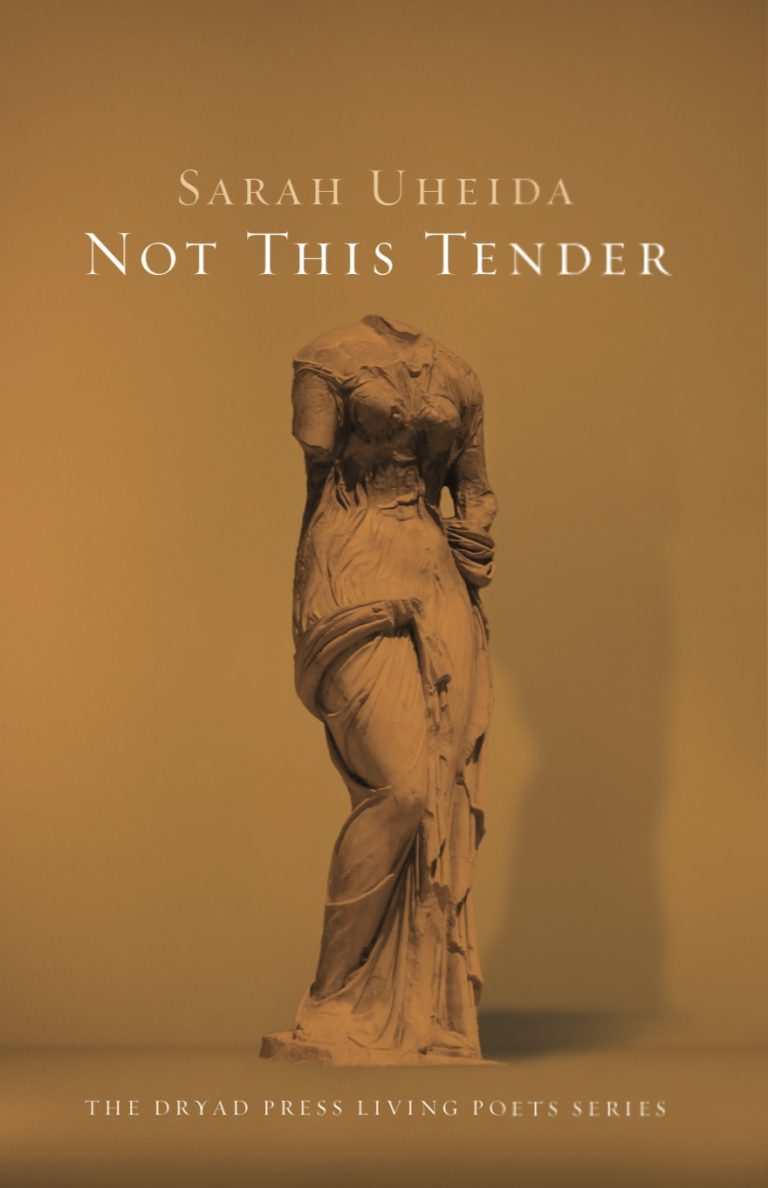

The cover of Not This Tender really stands out. Can you share the story behind its design? Did you have a particular emotion in mind that you wanted the cover to evoke in readers before they even opened the book?

The cover is a sculpture from the Nymphaeum in Sabratha, Libya — my hometown. I saw it often as a child, but only rediscovered it a few years ago. I love it. It felt like the right feeling for Not This Tender. The image is mythical, architectural — but also deeply personal. That space, like the book, holds absence and presence at once. I wanted the cover to feel atmospheric, like a threshold. Something that invites you in without explaining itself. A landscape that looks like it’s waiting to be entered.

Looking ahead, how do you envision your poetry evolving? Are there new themes or forms you’re interested in exploring in future projects?

Yes — I’ve been working on a new project, a collection of lyric essays, where I explore language and time, especially through the lens of desire: familial, ontological, migratory, erotic, and artistic desire. The working title is I Will Have Been Loved, and it plays with tense and translation — how we live inside grammar. Arabic, for example, doesn’t have a present-tense “am,” and that changes how identity is expressed. I want to think through those differences. I’m interested in voice, in echo, in the poetry that’s in everything — and in how we speak differently depending on where we hurt.

If you could invite readers to carry away just one feeling or insight from your book, what would it be?

That tenderness can be radical. That survival doesn’t always mean endurance — it can also mean beauty, attention, literary pleasure. And that memory — even fractured, unresolved, in translation — can still be a kind of shelter.